I was reared in the golden days of the Bronx where one’s greatest dilemma was whether to see the Yankees or the Giants play baseball. Always interested in sketching, at about age eleven I borrowed an album from my local library with an interesting drawing of a man deep in thought on the cover. I took it home to copy to improve my own drawings. Then I decided, what the hell, I might as well play the record even though I had never heard of the composer. It was Tchaikovsky’s fifth symphony. I was blown away. I had never heard music like it. I promptly returned to the library for more and began working my way through their extensive collection of classical music. What immediately occurred to me was, how did people create such incredible melodies? Thus, I became hooked on creativity. But in those days if you were smart, or thought you were, you studied physics.

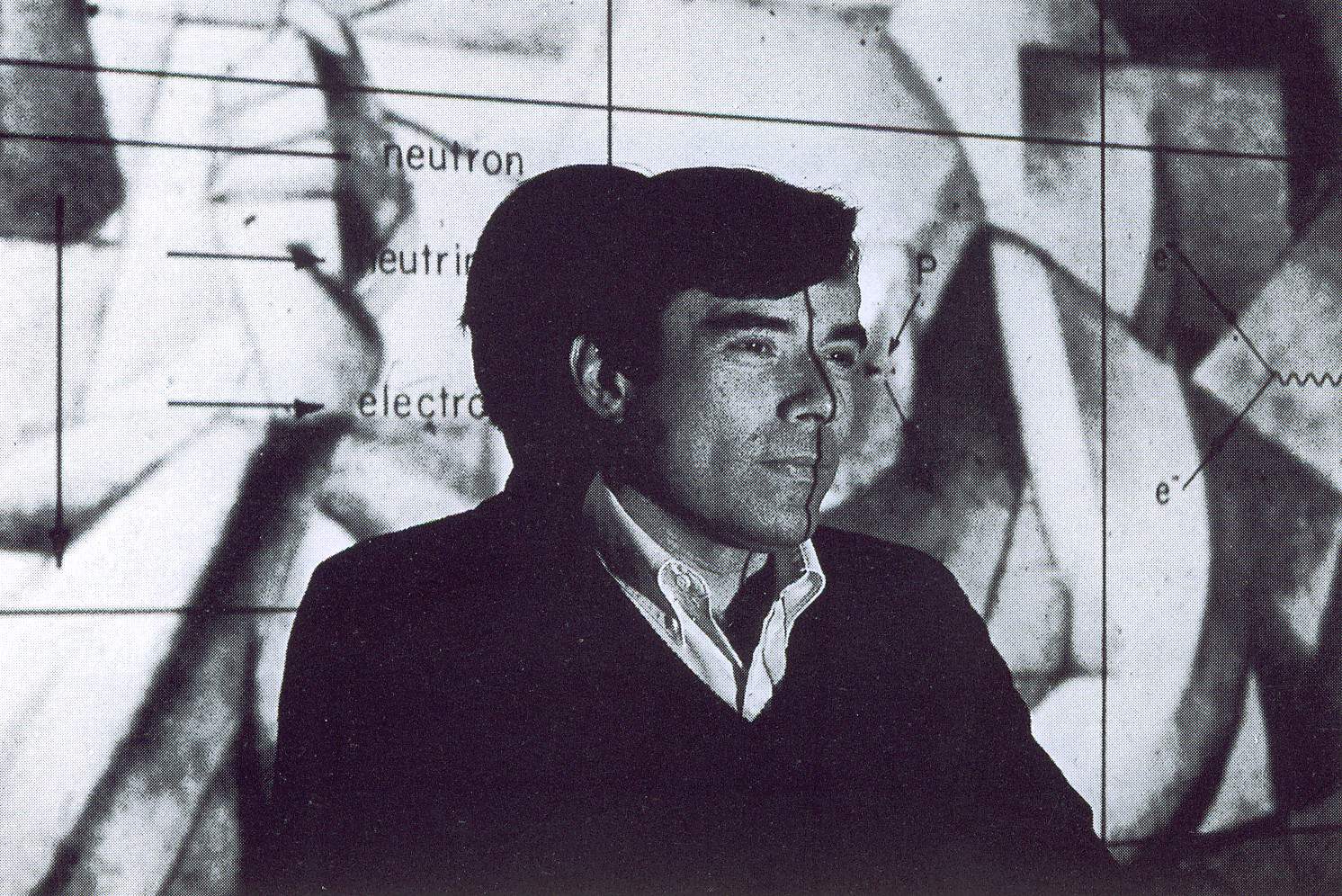

I spent an eye-opening four years at the City College of New York (CCNY – now CUNY) where I studied physics with heavy doses of philosophy. Then I forsook the wonders of Manhattan – particularly Greenwich Village – for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in Cambridge, MA. There I earned a PhD in physics. The theory of elementary particles was my interest but, as always, my passion was the “What is the Nature of…” questions, such as What is the nature of creativity? So it was inevitable that I would change directions and take the leap into the history of ideas. Reading the original German-language papers written by giants of twentieth-century physics – such as Albert Einstein, Niels Bohr, Werner Heisenberg and Wolfgang Pauli – drove home to me the importance of visual imagery in highly creative thinking. I became interested in how visual images are constructed and stored in the brain and how they are accessed and manipulated when we think.

Developing a Theory of Creativity

Cognitive science gave me the means to structure my ideas, particularly the metaphor of the brain processing information as if it were a computer. What struck me was this: we know the brain is creative; but can machines too be creative?

My interest in scientific creativity led to my investigating concepts such as intuition, symmetry and beauty. I went on to study the relation between art and science and between artistic and scientific creativity.

My method of looking into creativity and the creative process is to examine the histories of some of the world’s greatest scientists and artists. Then I investigate how theories of psychology and cognitive science can shed light on these scenarios. Seeking out what they have in common is a way of discovering how the brain works at its most creative.

To begin to understand the all-important role of unconscious thought in the creative process I formulated my Network Model. Then I developed a wider theory of creativity. I suggest that creativity is a two-step process: (1) the production of new ideas or artifacts from what is already known, which is (2) accomplished through problem solving.

We judge the creativity of a new idea or artifact by the degree to which it is surprising, novel, complex and ambiguous. These are subjective judgments and must be handled with care. But what drives the creative process? What are the dynamics behind creativity? I’ve isolated several characteristics of creativity: competitiveness, unpredictability, emotions, awareness and consciousness, among others.

Astonishingly my theory of creativity turned out to apply to machines as well.

My quest for the secret of creativity underpins my books. In Imagery in Scientific Thought: Creating 20th-Century Physics I investigate the role of visual imagery in scientific discovery as well as how historical research can be grist for theories of cognitive science and psychology which, in turn, can shed light on the creative process. Insights of Genius: Imagery and Creativity in Science and Art looks further into the role of visual imagery in creative thinking as well setting the groundwork for my Network Model and the beginnings of my wider theory of creativity. Einstein, Picasso: Space, Time and the Beauty that Causes Havoc, is the parallel biographies of Einstein and Picasso, focussing on their most creative years, 1905-1915 in which I apply my Network Model as well as elements of my still evolving wider theory of creativity. In Empire of the Stars: Friendship, Obsession and Betrayal in the Quest for Black Holes, I tell the story how the Indian astrophysicist Subrahmanyan Chandrasekhar discovered black holes in the face of his scientific and psychological battles with the brilliant British astrophysicist Arthur Stanley Eddington. 137: Jung, Pauli, and the Pursuit of a Scientific Obsession explores how Jung and his psychoanalysis helped Pauli to understand his creative powers and to cope with his complex life. In Colliding Worlds: How Cutting-Edge Science Redefined Contemporary Art I discuss the exciting new movement in which artists employ and illuminate the latest advances in science. And in The Artist in the Machine: The World of AI-Powered Creativity, I explore the controversial topic of machine creativity, focussing on AI-created art, literature and music.

***********

For some years after my PhD I was on the faculties of the Universities of Massachusetts and Harvard. In the meantime I was globe-trotting and decided to emigrate to England – I like to think that I was reversing the brain drain. From 1991 to 2005 I was Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at University College London, where I founded the Department of Science & Technology Studies.

I have lectured and written extensively on my research in the history and philosophy of nineteenth and twentieth century science and technology, on cognitive science, scientific creativity, the relation between art and science and on Artificial Intelligence, particularly machine creativity, focussing on AI-created art, literature and music.

I am very proud that some honours have come my way. I am a Fellow of the American Physical Society, a Corresponding Fellow of l’Académie Internationale d’Histoire des Sciences, and was awarded fellowships from the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation, as well as grants for research from the American Council of Learned Societies, National Endowment for the Humanities, National Science Foundation, Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique and the Fritz Thyssen Stiftung. I was also an Associate Editor of the American Journal of Physics.

During 1977-1978 I was visiting professor at L’École Pratique des Hautes Études, Paris. I was Vice Chairman, Division of History of Physics, American Physical Society for 1983-1984, and Chairman for 1984-1985, and have been a Director of the International History of Physics School at the Ettore Majorana Centre for Scientific Culture, Erice, Sicily.

I have appeared on numerous television and radio programmes and was the science presenter on WGBH’s NOVA production, “Einstein.” I frequently consult on science productions and have written for the New York Times, the Guardian, Wired, American Scientist and Nautilus.

I now spend my time writing, lecturing and travelling.

I live in London with my wife, the author Lesley Downer. Not bad for a guy from The Bronx.